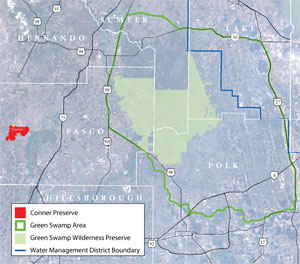

Top: Silage cutters harvest native grass seeds from the Green Swamp to be used at the Conner Preserve. Bottom: Portions of the Green Swamp and Conner Preserve are both located in Pasco County and have similar soil content.

Top: Silage cutters harvest native grass seeds from the Green Swamp to be used at the Conner Preserve. Bottom: Portions of the Green Swamp and Conner Preserve are both located in Pasco County and have similar soil content.

Hunters at the District’s Green Swamp property may have been surprised to see farm equipment rolling through the swamp’s uplands this winter, but it’s all part of the District’s land management restoration efforts.

The equipment harvested seeds from native grasses such as wiregrass and broomsedge for use at another District site being restored to its natural state. In this case, the seeds were being harvested from the Green Swamp and planted at Conner Preserve in Pasco County. Like other uplands on District lands, the preserve was cleared and used for pasture before the District acquired it. Nonnative grasses such as Bahia and Bermuda were planted for cattle forage, then other exotic grasses such as cogon and Natal grass invaded the disturbed areas.

“Native grassland is diminishing throughout the state,” said Mary Barnwell, senior land management specialist. “The loss of native grass impacts the wildlife that feed on it or use it for nesting and cover requirements.”

In addition, many nonnative grasses don’t carry fire during the growing season as well as native grasses do. Growing season burns promote higher biodiversity, maintain transitional wetland zones and create a rich landscape texture. The majority of Florida’s native plants and animals are dependent on fire to maintain the balance of the ecosystem.

The restoration process begins with planning and preparation.

“It takes us about two years to properly prepare the site for restoration,” said Barnwell. “We remove the Bahiagrass using a combination of methods, including burns, herbicides and discing the land.”

Nancy Bissett, a restoration ecologist with The Natives, Inc., who works with government agencies and private businesses throughout the state to plan and complete various restoration projects, is brought in once the site is ready.

Bissett’s team harvests with green silage cutters, which are large farm machines equipped with cutting blades in the front. They cut the seed and stems and then blow it through a chute into a tractor-trailer attached behind it. The harvested seed is then hauled to the seeding site.

According to Bissett, the District was the first state agency to begin using this process in its restoration efforts in 2001. Bissett began using the process at phosphate company restoration sites after a successful test site in 1994.

“We also use a brush harvester, but I find this process works better,” said Bissett. “We can collect a greater diversity of species and more seeds of each with this method.”

Native grass seed is only harvested once or twice from a District site before the site is “retired” to prevent adverse impacts to the donor site. The District uses all of the seed harvested to restore District land.

Additional varieties that cannot be harvested by machine are also hand-collected by The Natives, Inc. and added to the plant mix. These species add more diversity and help to ensure success with easier germinating seed. Some of the grasses that are hand-harvested include lopsided Indiangrass and love grasses.

Some of the farm equipment used to plant the native grass seed has been adapted from its original use. Wade Cooper, who has worked with Nancy since 1993, adapted a machine made to plant Bermudagrass so it will keep the plant material and seeds together.

“He’s made several different adjustments over the years before he found the right fit,” said Bissett. “In the past, you could see the seeds blowing away when a front came in, but now the seeds have a greater chance of taking root.”

The success rate also depends on rainfall. Part of Conner Preserve was planted last year, but fewer plants took hold, most likely due to the lack of rain.

Once the site is seeded, the District must maintain and care for it for several years.

“We rely on District terrestrial exotic and mowing crews, as well as contractors, to help us kill the exotic species and keep the weeds under control,” said Barnwell. “Then in a few years, we will burn the grasses to encourage flowering, seeding and spreading of the desired native species.”