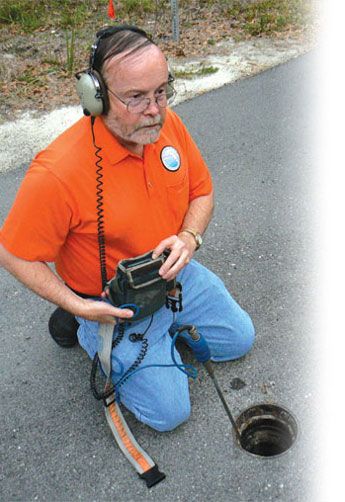

Carl Wright, senior water conservation analyst, locates leaks by using an acoustic listening instrument.

Carl Wright, senior water conservation analyst, locates leaks by using an acoustic listening instrument.

It’s the ear, not the eye, that locates costly leaks in public supply water distribution systems.

“If you were relying on water coming to the surface to tell you where there was a leak, those things could go on unchecked indefinitely,” said Carl Wright, senior water conservation analyst for the District.

Wright operates the District’s Urban Mobile Lab, providing a free service to municipal water utilities to assist them in locating leaks — particularly those that do not present themselves aboveground.

Locating leakage from water distribution systems is increasingly important. The cost of water leakage in the U.S. is in the billions of dollars per year, and the true cost is considerably higher when factors such as property damage, liability and investment in limited water resources are included.

The solution is to implement an effective leak detection program not reliant on physical clues to locate leaks. The District’s program uses electronic equipment to identify leak sounds and pinpoint the precise locations of underground breaches.

“When water flows through an opening in a pressurized system, it creates vibrations that travel an indeterminate distance along the containment structure,” explained Wright. “These vibrations are the basis for sonic leak detection.”

Using an electronic instrument that converts vibrations to sound, Wright listens to access points along the distribution system for the idiomatic sounds created by a breach in pipes. Water mains provide the best sound reverberation. However, since they are normally buried and direct contact is not possible, Wright uses mostly valves and fire hydrants to gain listening access to the distribution system. Acoustic listening instruments can listen to flow noise through sensors coupled to a pipe magnetically, mechanically, or through the soil using a ground microphone.

The process of leak detection first surveys the entire system for “leak sounds.” Then each potential leak site is further investigated and, if necessary, a computerized leak correlator that works on sonic transmission (speed of sound) principles is used to pinpoint the exact location of the leak.

The correlator works by comparing how long it takes the corresponding sound pattern to reach two sensor points placed on the pipe on either side of the suspected leak position. A typical intersensor distance ranges from 300 to 1,200 feet. The sound arrives from the closer of the two sensors first. Then there is a “time delay” before the sound arrives from the farther sensor. This time delay, combined with knowledge of the distance between the sensors and the velocity of the sound in the pipe, enables the correlator to calculate the leak position.

Citrus County workers dig up the pipes to find the leak. After uncovering the leak, the workers fix it and fill the hole.

Citrus County workers dig up the pipes to find the leak. After uncovering the leak, the workers fix it and fill the hole.

“I program the correlator with the material and diameter of the pipe and the distance between the two sensors, and it is able to determine velocity and can deduce from that the location of the leak,” said Wright. “The correlator eliminates the need for extensive hit-or-miss excavation and the unnecessary destruction of expensive pavement.”

Several things impact how well a leak can be heard, the most significant being the piping material. Since current leak detection techniques rely on vibrations that travel from molecule to molecule along the wall of the pipe, the denser the wall of the pipe, the greater the distance leak sounds will travel. Cast iron, ductile iron, galvanized steel and copper pipes are all extremely dense and exhibit excellent transmission qualities. Concrete pipe, or transite as it is often called, is not as dense and dampens vibrations more quickly than metallic pipes. Due to their lack of density, PVC and polyethylene pipe absorb, or attenuate, vibrations rather rapidly also. As a result, leak sounds do not travel great distances on these plastics.

“I don’t hold as much confidence in the correlator’s findings when they’re plastic pipes,” said Wright. “But it’s still not usually far off the mark.”

A water leak is continuously trying to tell you where it is located, according to Wright. Water exiting a line may rumble, whistle, hiss or, in some cases, whisper, but it is continuously sending out an audible cry for help.

“Finding a water leak is knowing how and where to listen and what to listen for,” he said.