On a stifling hot July morning, Paul Elliott, a senior land manager with the District, and Robert Jarrard, a local outdoor enthusiast, traveled deep into the Green Swamp to place a new grave marker at the site of a shocking and gruesome double murder that happened almost 90 years ago.

The bodies of Isham and Sarah Stewart were discovered in May of 1918. The coroner’s report stated they were killed in their beds with an ax, at least a week before they were found.

The discovery of the bodies made headlines and prompted numerous rumors about what happened.

Jarrard, who spends a lot of time in and around the swamp hunting and taking wildlife photos, read about the Stewarts and visited the homestead. The site, which sits in the southwest corner of Lake County, is part of the District’s Green Swamp Wilderness Preserve.

“I heard conflicting stories and when I visited the gravesite, the stones were not legible,” said Jarrard. A makeshift marker also at the site appeared to have the wrong year listed. “I had to find out what really happened and tell everyone about it.”

In his search for the facts, Jarrard came in contact with Judy Stewart Kroker, who is the great-niece of Isham Stewart and is interested in genealogy.

“I came out here with my granddaughter when I was researching the murders in 1998,” said Kroker. “There are a lot of Stewarts in this area, but none of them are into genealogy.”

Kroker says she spent all day trying to find the homestead but no one seemed to know where it was.

“I finally came upon a hunter in the woods and he drew me up a quick map,” said Kroker.

She shared her transcripts from one of the trials, photos and some interesting background information with Jarrard.

“Isham Stewart spent most of his life as a bachelor and a horse farmer,” said Kroker. “Sarah, who was called Sallie, was older than him and had children from a previous marriage. They married late in life and didn’t have any children together.”

Josh Browning, Sallie’s grandson, and his friend, John Tucker, were accused of robbing and murdering the couple. The four trials, two for each murder, revealed confusing and sometimes conflicting witness testimony and details that did not fit with either man’s alibi.

Witnesses testified that Browning and Tucker were seen talking together at the train depot about a week before the Stewarts’ remains were found. Other witnesses placed them on the road that led to the Stewarts’ homestead, which was at least 15 miles from Richland. However, Tucker claimed he never talked to Browning and had spent the day working in the woods before he stayed the night at a relative’s home.

Perhaps the most telling testimony came from Browning’s mom and another woman, who testified that he asked his mother if his stepgrandfather really did take his money out of the bank.

No one can say who did what at the Stewarts’ cabin, but testimony shows that the two men went there together to allegedly rob them.

During the week after the murder, but before the bodies were found, Browning went to St. Petersburg, and one of Tucker’s relatives was seen with $121 that she said Tucker had given her.

It was a gruesome scene when the bodies were discovered.

“According to the sheriff’s report, the man who found them said there were vultures on the roof,” said Jarrard. “Browning’s dad and uncle were originally arrested for the murders when Browning came driving up to the inquest in a brand new car.”

Josh Browning and John Tucker were eventually arrested and, after each standing trial twice, both men were found guilty of murder. They were each sentenced to a total of 20 years in prison, 10 for each murder.

Jarrard brought the details to Elliott, the District senior land manager, who had also heard conflicting tales from area residents about the murders.

“Some of the old-timers in the area remember the murders, but not everyone agrees on who committed the murders,” said Elliott. “In fact, some people thought some of the Stewarts’ cousins from the Brooksville area did it. When I talked to Jarrard and saw the documentation, I thought it was important to have the correct historical information at the site.”

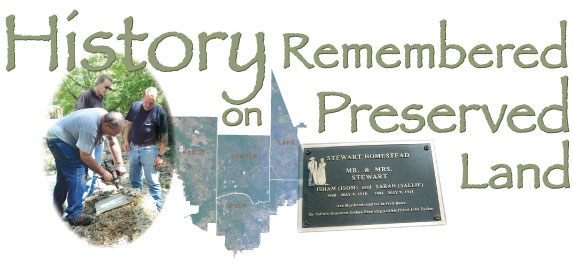

Elliott received approval to put a new and accurate marker near the gravesite.

Kroker and her husband, Fred, drove from Seminole County to observe Elliott and Jarrard place the new marker at the site.

“If these trees could talk, I bet they could tell us exactly what happened,” said Fred Kroker.

Ed White, one of Jarrard’s hunting companions, also accompanied Elliott and Jarrard that morning. He and Fred took turns helping Elliott drill the holes to secure the marker to a rock that was recently placed at the site.

“Back then it was such a shocking crime,” said Kroker. “They came from so far to do it too.”

“If you think about it, back in those days it would take someone all day to get to Dade City,” said Elliott. “The state has changed so much in the past 90 years.”

And while the state is developing at a rapid pace, the land where the Stewarts lived and died remains very similar to how it was in 1918 because the land is part of the District’s preserve.

“This really means a lot to me,” said Jarrard. “I love being out in the swamp, and it makes me happy to see our efforts come to a conclusion. I am sure it will also be of interest to everyone who uses this land for outdoor recreation.”